The Japanese Dog: Branding and Mental Images

The concept of “the Japanese dog” is intriguing. Dogs are so much more than just dogs, and clearly this has always been the case. During the past 100 years, various “brands” have been built and used to promote the Japanese dog. I don’t get a similar feel from the Finnish dog breeds. A good working hound is a good working hound, and that’s always been enough. Maybe this is exactly what explains the difference?

For the general public, the Japanese dogs had already lost their original status as valuable hunting dogs before their preservation efforts began in the 1920s. Something else had to be invented to make them important again. In what light have the Japanese dogs been presented over time? These observations come from a Japanese-illiterate Western female and are based on the fragments of history that have been captured on the pages of Shiba Inu Library.

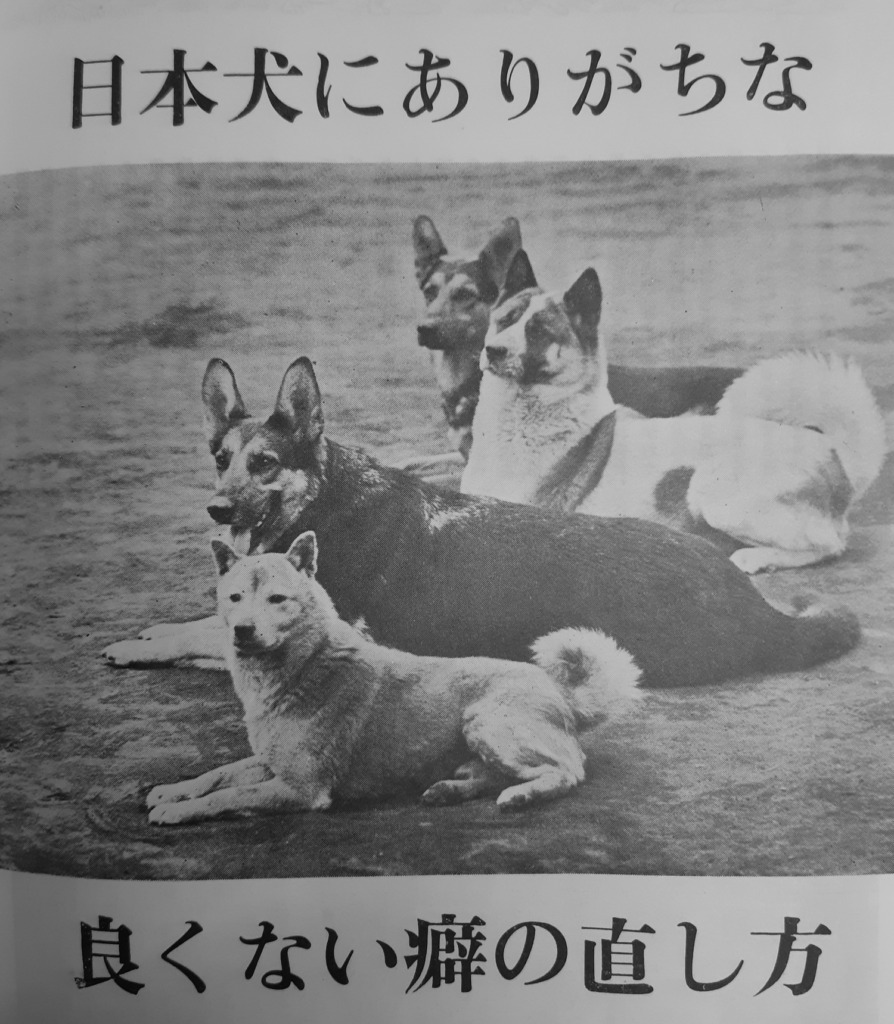

The Japanese Dog = Superior Working Dog

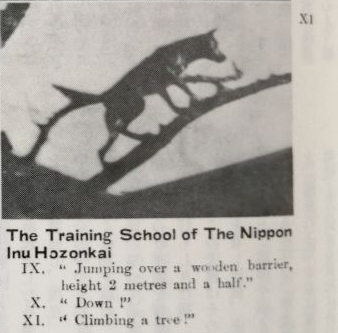

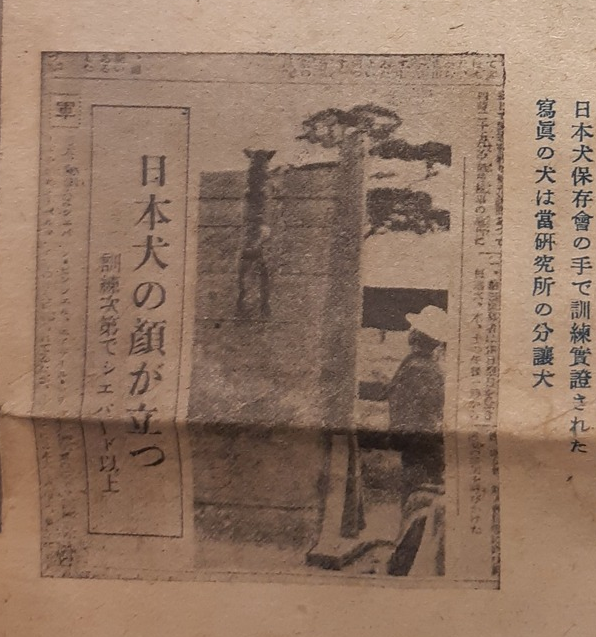

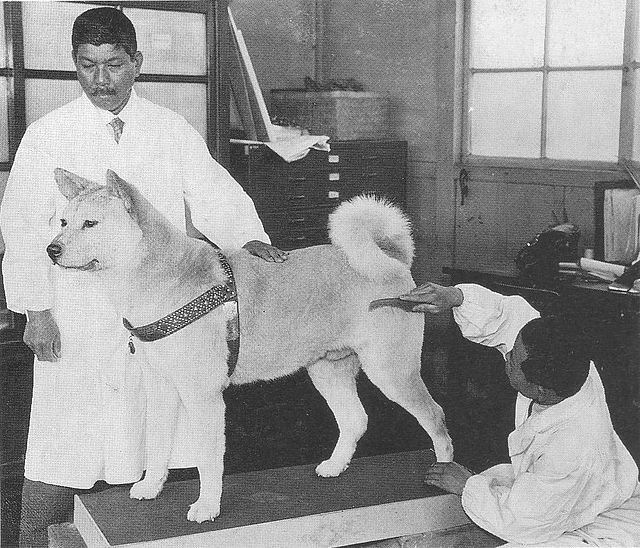

The earliest material in the Shiba Inu Library dates back to 1930—very close to the start of the Japanese dog phenomenon. Is there a pattern in the representative images? Yes. Photos of sporty dogs climbing ladders and over high walls, repeated again and again. This was done not only by the commercial Shiba Inu Research Center to advertise puppy production, but also by NIPPO when they approached Western countries to introduce the Japanese dogs. Written descriptions made them sound like the Jeeps of the dog world—suitable for hunting, but apparently also for almost any task that required a working dog.

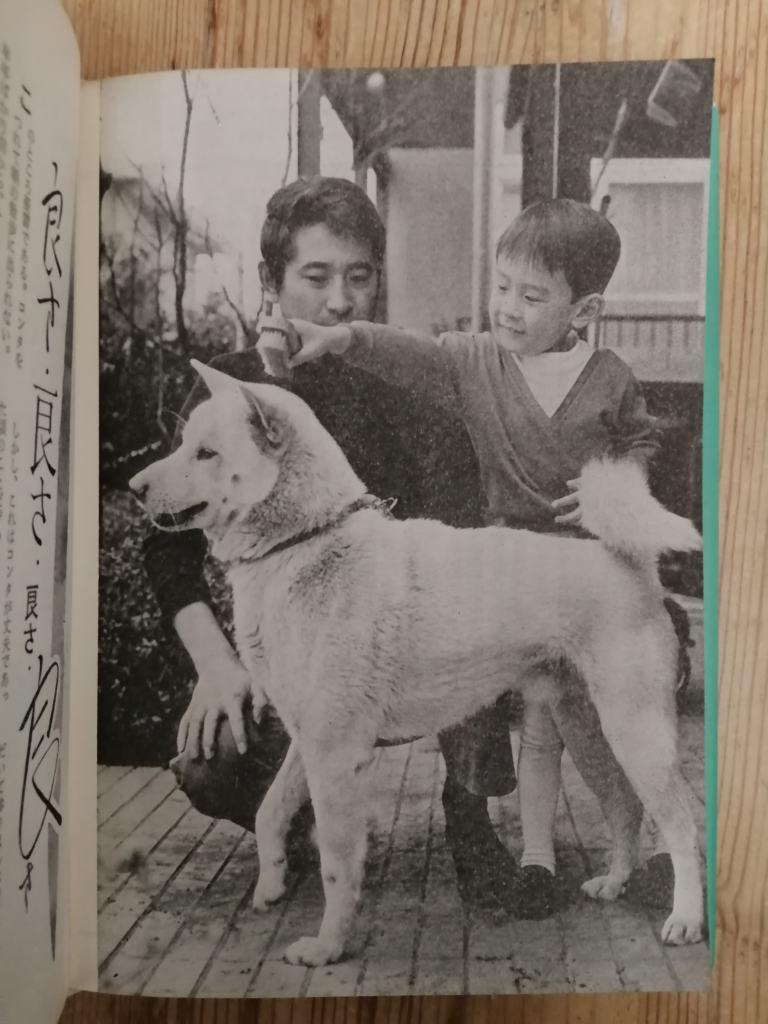

It does raise a question, though. For how long were German Shepherds selectively bred before they became reliable and obedient working dogs? Japanese dogs had been on the verge of extinction a moment earlier. Their owners and breeders were, naturally, men. If the timing is not indicative enough, there’s a specific mention by Mr. Takahisa, in the context of the small Japanese Terrier, that “even women and children like them.” The working dog phase continued surprisingly long. Interestingly, the Swedish Shiba pioneer Inga Carlson of kennel Manlöten said that she was particularly struck by portrayals of the Shiba as a working dog. She did not expect to get hunting dogs when she imported the first famous Shibas to Europe in the early 1970s. The conclusion: the Shiba was no longer marketed as a hunting dog, but rather as a working dog. In Sweden, her Shibas actually performed very well and were even considered groundbreaking. You did not usually see small dogs on the obedience field.

The Japanese Dog = Source of Masculine Pride

Hachiko luckily occurred around the same time as the Japanese dog boom. The rise in nationalism boosted the appreciation of native dogs. It looks like these three factors entwined more or less together. Hachiko’s loyalty to his master may have been interpreted more literally in the West. At least valuable dogs were bought, sold, received, and gifted from master to master quite freely in Japan. As for Hachiko, an alternative reason for him to retain the habit of hanging around the station for all those years was because he and other street dogs were being fed with food-stall leftovers.

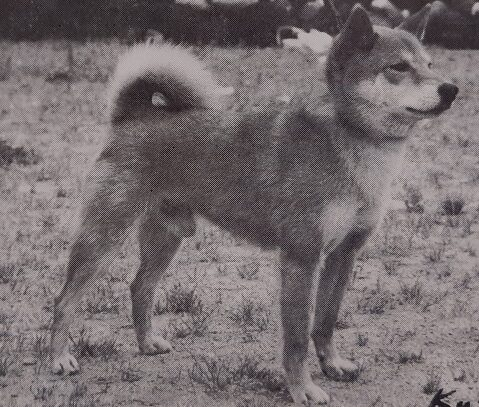

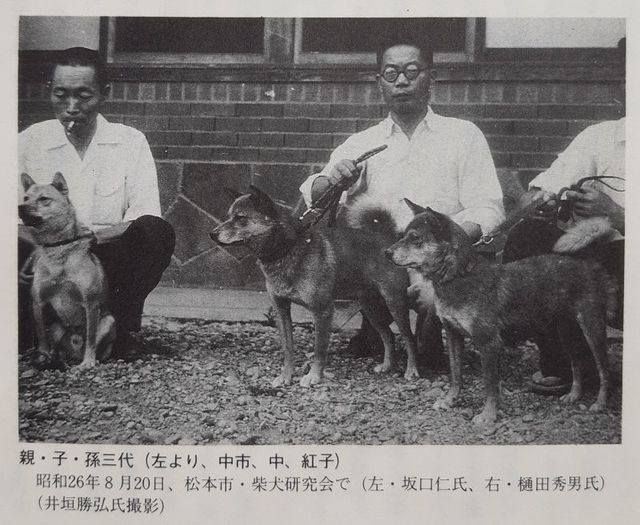

Anyway, at some point the preservation movement proceeded to define an ideal Japanese dog. Terms like kan’i, ryūsei, and soboku were chosen to encapsulate their essence. Dogs stopped climbing ladders and walls in photos. Perhaps it was enough that they embodied those qualities by standing in a show ring and glaring at each other. But whether it was their abilities or noble essence, pictures still aimed to make an impression. One of my favorite photos is from the early ’50s, showing the three foundation dogs of the modern Shiba and proud Japanese men beside them. It is this very photo I tend to return to whenever I wonder what, exactly, is the original ideal Shiba worth preserving. These men still need to be willing to appear in the same shot with their Japanese dogs. You can imagine today’s dogs in that picture. If men in other countries die from laughter and these guys die from shame, then perhaps the preservation of the Japanese dog is not going as it should.

Branding Japanese Dogs in the West

I’ve already written about this in the “Mythbuster” series. “Primitive and healthy breed not bred for dog shows” was my view of Shibas for a long time, 10–20 years ago. That image must have originated from somewhere, but I no longer remember the sources. But I do remember that as recently as ten years ago, doing any dog sports just for fun with a Shiba was considered a miracle. They were so stubborn and difficult to motivate! This is interesting, because (1) the early working dog brand had done a full flip and (2) during my ten years as a Shiba owner, the trend has again reversed: apparently you can do dog sports for fun and even successfully compete with them.

And then there’s the Nordic phenomenon Ginga Nagareboshi Gin. I asked in a Finnish Akita Facebook group how people first came to know the breed. The overwhelming winner was Ginga. Well, almost everyone watches it as a kid around here, so the survey result would probably have been the same in any Finnish group. I wonder if anyone in Japan realizes in what context their national dogs are introduced in some of the most dog-loving countries. I believe it’s something the pioneer friends of the Japanese dog would have accepted.

The Japanese Dog = Cute, Round, and Fluffy Ornament for Social Media

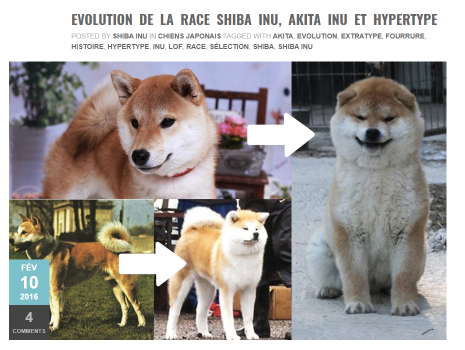

From the header photo of the now-defunct blog Shiba Inu et Chiens Japonais. I’m reposting it because this ten-year-old vision has come true. Credit to the unknown photographers and the original blogger. Japan these days is renowned for its kawaii culture, where cuteness is valued. And I see that cuteness has swallowed up Akitas and Shibas. Those former working dogs and sources of masculine pride are now dressed up and posted on Instagram by women 😄

An extreme form of tiny cuteness is the “Mameshiba.” Western Shibas express an even weirder desire for thick roundness. I’ve complained about this before because I simply don’t get it. What is it that urges people to create and buy spherical animals? They don’t even need to be brachycephalic breeds. Legs shorten and disappear into fluffy long-hair coats (the trait being incompletely dominant in carriers), ears shrink, and the muzzle shortens because such protruding parts would interfere with the round appearance. Luckily, physical appearance can change quickly—also back the other way. It will be interesting to see the next brand after the cuteness phase gets old. Whether or not the middle-sized Japanese dog breeds can survive without going through this round & cute transformation is another question.

The Japanese Dog – This Just In

This snippet is from the official NIPPO Instagram channel. They advertise the Grand National Show of 2025. Notice the use of adjectives. What do you think?